LUFS, Loudness and Levels

Mixing sound to Broadcast Audio specification: EBU R128, and what are even LUFS, anyway?

If you’re wondering how to delivery compliant audio for broadcast in the UK or Europe, here’s an explanation of LUFS, EBU R128 and loudness to help you understand and meet the criteria.

In this article I’m going to cover everything you need to ensure your audio is UK and European broadcast specification, what to measure, and why.

There’s a lot of detail, so if you’re not interested or don’t have time, feel free to skip to the end!

You can also check out the cheatsheet here.

Background

Measuring loudness is not simple.

We perceive loudness differently depending on the content of the programme material, as our ears are more sensitive to certain frequencies than others.

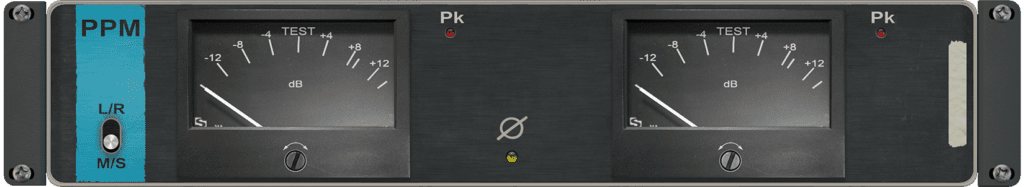

Back in the bad old days of post production audio, the level of audio was regulated only by peak volume.

As an example, BBC PPM metering was used, PPM4 (0dBu) being the set limit for programme volume, equating roughly to -18dBFS.

While this was used for a very many years, it did not truly consider or measure loudness, only peak volume.

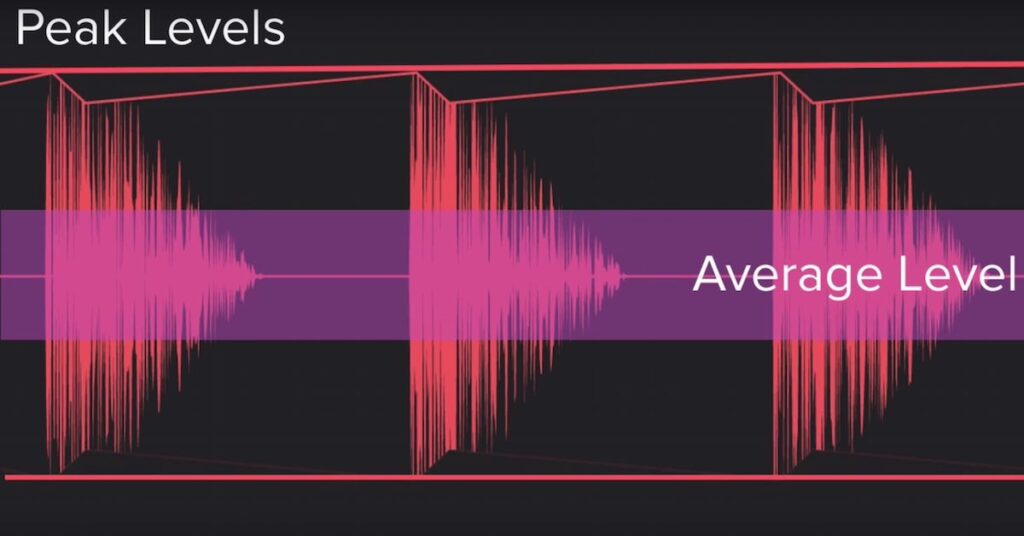

So, what is peak volume?

Peak volume is the maximum level that an audio signal can be within a defined system.

Which is very much not the same as average level.

The average level is closer to what we experience as ‘loudness’.

So, what’s the problem?

This flawed measurement method gave rise to significant differences in volume between programme material, particularly between scheduled programmes and television commercials (TVCs).

Since it was possible to achieve higher average level with severe compression and limiting without exceeding the prescribed peak limit, audio engineers of the day (1990s to early 2010s) would absolutely slam the adverts into compression and limiting, making the advert as loud as possible.

This phenomenon was known as the loudness war. It was understandable from the advertiser’s point of view – having spent significant sums of money on broadcast advertising, who would want to be quieter than the competition?

While longer format programme material would tend to be reasonably conservative with loudness, an increasing number complaints came in from viewers as they saw massive differences between the (for example) nature documentary they were watching, and the positively slammed TVC that interrupted it.

The solution

ITU recognised that a more meaningful way to measure loudness was needed to curb the manipulation of peak monitoring, that had given rise to the unacceptable variation from programmes to TVCs. Loudness Units were born (LU), and integrated into a standard. Being an international standard, this was given a snappy name.

Enter ITU-R BS.1770.

On the back of this standard, the European Broadcast Union (EBU) drew up a set of recommendations, resulting in EBU R128.

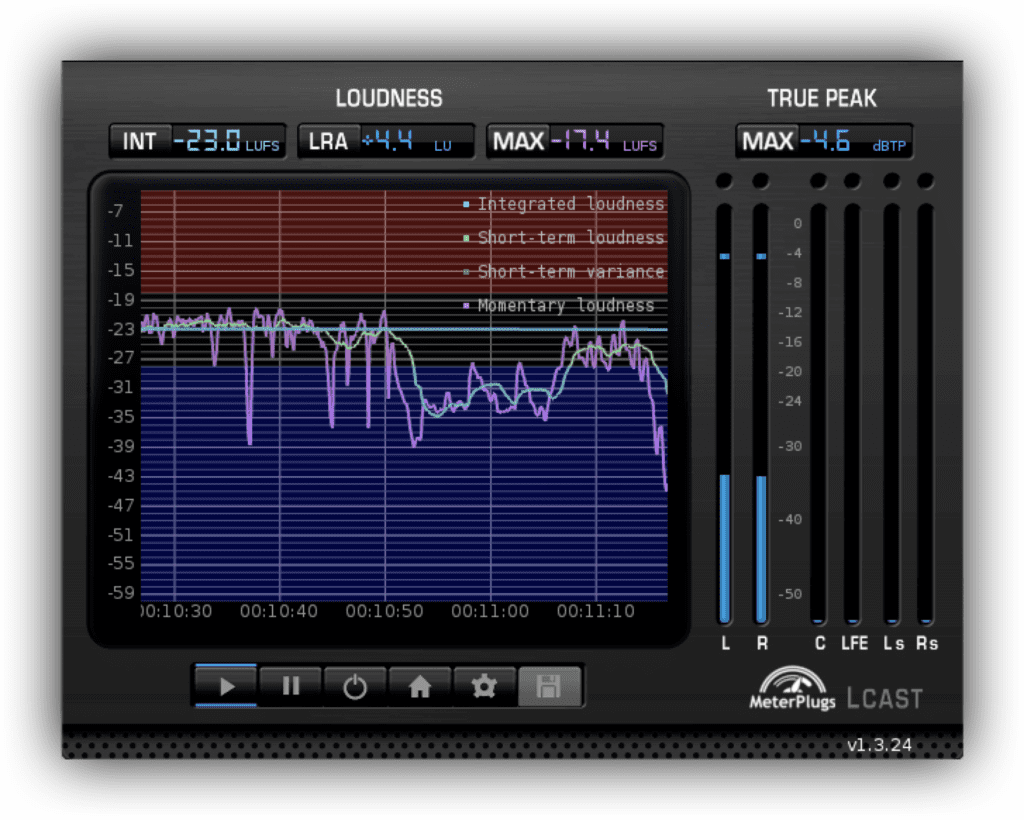

This prescribes -23 LUFS as the recommended broadcast standard, and has subsequently been adopted by all self-respecting broadcasters in Europe, as well as many other countries around the world.

What are Loudness Units, and why do I care?

Loudness Units measure the average level over the entire duration of the programme, and take into account the ear’s sensitivity to different frequencies.

As such, LU is a very effective way to ensure that the perceived average loudness is the same for any given programmes adhering to the same Loudness Units, Full Scale (LUFS) value.

What’s the difference between LKFS and LUFS?

While the ITU named LKFS (Loudness, K-weighted, relative to Full Scale), the European Broadcast Union produced their equivalent term, LUFS, citing the failure of LKFS to comply with scientific naming conventions, specifically those set out in ISO 80000-8.

Since measurement must be a scientific, reliably reproducible activity, it is somewhat baffling and disappointing that the ITU chose to disregard well documented and widely adopted scientific naming conventions.

LUFS and LKFS are one and the same thing.

One tends to find LKFS in use in North America, for example Netflix, Amazon Prime, Disney+ Paramount+ et al, all use LKFS in their loudness specifications, while the rest of the world tends to use LUFS.

The US has a penchant for sticking with antiquated measurement systems however (ahem, imperial), so, perhaps it should not be surprising that the country is not too bothered about using standardised scientific terms for measuring audio. To be fair though, they were led astray by the Swiss ITU. Tsk!

Getting down to brass tacks

To mix for UK and European broadcast, you need to be mixing to -23 LUFS, while never exceeding peak level of -1dBTP.

Simply get yourself a LUFS meter (examples are below), measure over the full duration of the content, and make adjustments until the target level is -23 LUFS. There are some tolerances, +/- 0.5 LU is acceptable, so -23.5 to -22.5 LUFS will pass broadcast checks. However, some differences can exist with different meters, so to ensure compliance, I personally would not recommend submitting a mix at either extreme end of the tolerance window.

Great! I’ve mixed my TVC to -23LUFS, and hard limited to -1dBTP, it’s going to pass!

There is one additional requirement for TVCs, in the UK at least.

Advertisements are required to have 6 frames of silence at the beginning and the end of the spot.

If you have been sent a mix that doesn’t include this silence, you must introduce it. If you don’t, it will fail broadcast checks!

I’ve mixed something for online use that now needs to go to broadcast, can I just drop my level to -23 LUFS?

Technically you can, but you probably should re-mix it from scratch to yield better dynamics! The compression required to meet -14LUFS or other online loudness levels, will mean that overall your mix won’t have as much variation as it could do. For longer programme material, this means that your mix may be fatiguing, and for all durations, it means that you are missing the opportunity for louder moments in your mix.

This might seem counter-intuitive, but don’t forget that the loudness is measured as an average. By using quieter moments in the programme, you have the ability to drive some moments louder, making them more impactful. Think of it as a budget – you can consistently hit -23 LUFS all the way through, or you can run lower in places and save some for key moments. Consistency is important, too, so you don’t want to be wildly varying in volume, but in my experience a good mix is emotive, and that means dynamic variation.

For a number of reasons, I tend to mix most projects at -23 LUFS and then add an extra Limiter, a Waves L2, on my stereo bus to bring the audio up to level for online.

This means that, if the client initially requested a mix for online and later require a broadcast specification mix, I don’t have to remix the whole thing.

The only exceptions to this are when I am working on Video On Demand (VOD), where I generally need to meet either -24 LKFS or -27 LKFS, or when I am mixing for cinema, 5.1 and so on.

But those jobs tend to be very obvious from the outset. Even if I’m wrong, it’s much easier to get from -23LUFS to -27LKFS, than -14LUFS to -27LKFS, an enormous difference in dynamic range!

OK, I get it. But what happens if I’m over or under the allowed audio level?

In the world of broadcast, videos must pass stringent tests, so you can expect your content to be rejected for broadcast if it fails.

That will mean you or your client will get a report stating why it failed the requirements. Obviously you want to avoid this in all cases, so it’s worth ensuring you meet all requirements. Professional sound engineers and dubbing mixers know what the specs are and will always ensure your audio passes first time.

The issue usually arises with less experienced audio engineers or editors, who lack the knowledge and experience to meet these loudness specifications.

Online, it’s like the Wild West; everyone has their own “standard”.

The nice thing about standards, is that there are so many of them!

Some platforms, like YouTube, will turn your level down if it is louder than their standard.

But, they won’t turn it up.

Tip – you can check any video on YouTube to see how close they were tot he targ, right click the video in your browser to bring up the video menu, then choose Video Stats For Nerds.

An overlay will be displayed over the video with a bunch of (useful?) stats.

Here you will find the volume / normalised item and in brackets you’ll see content loudness and a number in dB.

The content loudness figure shows how much the video was over the target loudness of -14 LUFS.

If a positive figure is shown, like 3dB, then the video was brought down by 3dB to meet the target.

If it is a negative figure, eg -2.4dB, then the video is 2.4dB quieter.

And, just to reiterate, YouTube does not turn up the volume of quieter videos, so this is will be quieter than comparable videos on the platform.

Recommended LUFS meters

MeterPlugs LCAST (link) $199 stereo / $399 Surround

Waves WLM Plus (link) $399 (frequently on sale though for around $40)

Youlean Loudness Meter (link) Free!

Nugen Audio VisLM (link) $449

If you’re a video editor, Premiere Pro has two Loudness Meters built in, see these articles for more information:

- https://helpx.adobe.com/uk/premiere-pro/using/loudness-meter.html

- https://www.tcelectronic.com/product.html?modelCode=HE005

Common LUFS / LKFS levels for different platforms and broadcasters:

-14 YouTube, Spotify, Tidal, Amazon Music

-15 Deezer

-18 iTunes (Apple Music)

-23 UK and Europe Broadcast

-24 Amazon Prime

-27 Netflix, Disney+

(Note that the tolerances vary for each broadcaster!)

While every effort is made to ensure these are accurate at the time of writing, you should always check the specification for the platform or broadcaster you are delivering to, for the country you are mixing for, and that these figures are correct at the time in future when you are mixing. Things can and frequently do change! 🙂

David Bartley is a freelance Audio Engineer and Sound Designer based in London, UK.